Messaging has been the primary use case and daily utility on mobile phones long before WhatsApp and Snapchat became household names. As early partners with pioneers like Siri, Hotmail, Tumblr, Glide, and Periscope, Menlo Ventures has invested in messaging and studied its history as part of a broader theme in communication for decades. Our human craving for interaction, expression, and understanding has remain unchanged, but technology has made it increasingly easier to convey our thoughts with speed and accuracy. First came text-based technologies like pen and paper, the telegraph, SMS, and WhatsApp; then image-based with hieroglyphics, photographs, Snapchat, Instagram, and Emoji, and finally video-based via Skype, FaceTime, YouTube, and GIFs. Our ongoing research culminated in a thesis on GIFs and a $10 million Series A investment in David McIntosh and Erick Hachenburg’s vision of creating the world’s first visual expression language. We couldn’t be more excited to share that news and our work with you today.

Text Message History

The evolution of online messaging behavior can be traced to Millennials, the weather vane for broad consumer adoption. Attention spans are shorter than ever in the instant gratification generation that grew up with web and mobile at their fingertips, so early adopters learned to maximize utility while minimizing time investment. The first affordable cell phones were purpose-built for voice communication, but it was the introduction of Short Message Service (SMS) in 1985 that became the “killer feature” attributed to mobile usage inflecting. For the first time, millions could communicate quickly, conveniently, and cheaply on-the-go with minimal behavioral overhead. The dominance of SMS has since been displaced by feature-rich and data-based messaging networks like Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp (whose users send 30 billion messages per day vs. 20 billion on the global SMS network), but the fundamental behavior persists. Platform-agnostic teenagers text each other more frequently than any other form of communication including face to face.

Texting is a superior substitute to time-consuming voice calls in our era of fractured attention spans and expanding social graphs, but it’s missing the full context of images and video. In the mid-2000’s, mass-market VoIP technologies capitalized on broadband proliferation and became a popular medium through services like Skype for consumers and Vidyo for businesses. Video is a distinct use-case that approximates face-to-face communication; both are high context and require high time investment (i.e., cost) through captive attention and synchronicity. Texting and video are diametric poles that demarcate two critical forces in communication: context and cost.

The void between low context/cost and high context/cost media gave rise to paradigms that maximize context and minimize cost.

Menlo’s Messaging Matrix

This prism helps illuminate the history and future of messaging. The X-axis marks the cost of creating and consuming content, including direct (infrastructure, hardware, services, utilities) and indirect (time, opportunity cost, mental/physical resources, synchronicity, captivity). The Y-axis marks the context derived from those costs, including timing, tone, tenor, emotion, and appearance, among other visual and verbal cues missing from denotative communication.

Each application has relevant use cases and network effects, but it’s easy to see why messaging share has migrated to low-cost/high-context platforms like Snapchat for consumers and Slack for enterprises. Users abandon legacy protocols for greener platforms that pack denser context into less time. Moving from the bottom to top row illustrates the key to unlocking usage: constraint. Users have a high bar to invest time creating and consuming content. Enforcing limits lowers the bar and breeds creativity and cadence, the foundation of what we termed the “snackable internet”: 722 original Emoji, 160-letter SMS limits, 140-character Tweets, 10-second Snaps, and now 3- to 5-second GIFs.

Enforcing these guideposts solves the high barrier to content creation and consumption observed in traditional media forms, where unconstrained length deters usage. Frequent usage is a proxy for retention and engagement, the prerequisites for habit formation and the cornerstone of consumer juggernauts. WhatsApp boasted a 72% daily user/monthly user ratio who open the app ~25x a day even at 450 million active users. Snapchat’s early adopters reportedly sent 10 Snaps per day.

Messaging is perhaps the ideal use-case and breeding ground for rapid adoption and usage: their users open apps ~25x a day compared to ~15x for broadcast platforms like Instagram and Twitter or ~5x a day for video platforms like YouNow according to a recent research report on Facebook. GIFs are another ideal format that can harness messaging as a daily use-case, but what sets them apart from other high-context/low-cost media is the potential to become a universal language.

Signs of the times

We have finite time to recount our intricate sentiments in sufficient detail, so users have sought ways to compress context using limited resources since the salad days of messaging. Not all expressions are created equal, even in conventional prose. The difference between “Yes.” “ Yes?” “Yes!?” and “YES!” is subtle, yet substantial. Even the most talented communicators have trouble deciding how and what to articulate at the right time, so we turn to visual aids wherever we can.

Emotion icons, better known as emoticons, are textual representations of emotion first observed in the 19th century. Nuanced feelings like joy 😀 sadness :’( and surprise o_O could be expressed in powerfully simple depictions still used in written letters, e-mails, and SMS to this day. These rudimentary hieroglyphics evolved into a functioning jargon that included everything from Homer Simpson ~(_8^(I) to Santa Claus *<|:-), the forefathers of a universal language most of us now speak fluently.

Emoji were conceived in 1997 as the first standardized supplemental layer to text-based communication and a universal language christened by Unicode in 2010. Given how much communication is connotative, Emoji’s intuitive meaning, elastic interpretations, and snackable format make them a ubiquitous stopgap between face-to-face communication and bare-bones text.

By appending itself to existing messaging networks and granting users a new superpower in their pockets, Emoji became a viral sensation seemingly overnight. Three-quarters of Americans and four-fifths of Chinese users surveyed have used Emoji or their sticker brethren in messaging apps. Used by an estimated 100–150 million users on iMessage alone, Emoji are now Tweeted more frequently than hyphens or the numeral 5. Its far-reaching influence even tilted the balance of the 2015 NBA free agency, whose juiciest drama was chronicled entirely in Emoji along with a fitting photo featuring Silicon Valley entrepreneur and NBA owner Vivek Ranadive.

While Emoji help plug the gap of creative expression, they have their limitations. As a static cuneiform governed by a consortium of overseers, they are devoid of the customization, specificity, and dynamic format of video. Thus Emoji move at the speed of the Oxford dictionary, i.e., glacially. Imagine revising an alphabet every month. Meanwhile, the vast universe of GIFs grows ever larger and faster absent the confines of linguistic protocol, but until now it’s been largely inaccessible without a cipher to index it.

The GIF that keeps on GIFing

The Graphics Interchange Format, known as a GIF in web vernacular, is a 3- to 5-second video clip that can be compressed into minimal file size without degrading visual quality. GIFs can be a superior format to text, images, video, and even face-to-face communication. By painting a vivid portrait and condensing its complexity into bite-sized punchlines, they can pinpoint sophisticated emotions with uncanny precision. Imagine how many times we’ve seen a movie or watched a show and thought, “I wish I could quote that scene now that I’m in the exact same situation.” The latent user behavior has been lying dormant, waiting for the right format and application to ignite it. GIFs are “the happy medium”: they empower users with an expressive language like Emoji, but an adaptable one that users can customize based on the whims of popular taste.

GIFs were first popularized in 1987, but have only recently exploded as a viral phenomenon. It was impractical to find and send the right GIFs at the right time. The only viable option was scouring the Internet or fast-forwarding through reams of old footage dusted off from YouTube, so GIFs found no permanent home as they roamed from site to site. Prominent web properties like Tumblr, WordPress, Reddit, and Imgur began to double as online repositories in the mid-2000’s, first for trending images and eventually for video memes as their popularity soared. The Internet needed time for its infrastructure, content corpus, and distribution channels to mature.

As we all know now, Moore’s Law waits for no one. The well-chronicled advent of smartphones catalyzed an unprecedented tectonic shift in consumer adoption.

GIFs made their way from web fans to media influencers and all the way to the White House as they infiltrated pop culture.

Unlike Emoji, millions of new GIFs can be uploaded every day, about everything and anything from American Idol to Jay-Z.

It’s easy to imagine the myriad possibilities for UGC and 3rd-party branded media: velfies, Vines, YouTube channels, TV, movies, shows, the list goes on.

From Tumblr to Reddit to ESPN and every corner of the Internet, it’s hard to avoid GIFs anywhere you look. It’s just hard to find the right one at the right time.

The world’s most vibrant library needs a catalog. Thanks to mobile bellwethers like Facebook, Snapchat, Instagram, and Twitter, visual communication has ridden extraordinary macro tailwinds. Storing, indexing, and searching video files has never been so practical and cost-effective. Consumers have acclimated to searching #metadata. Once Apple opened its keyboard SDK in late 2014, they unlocked the floodgates and set the stage for GIFs to enter the mainstream.

The key message

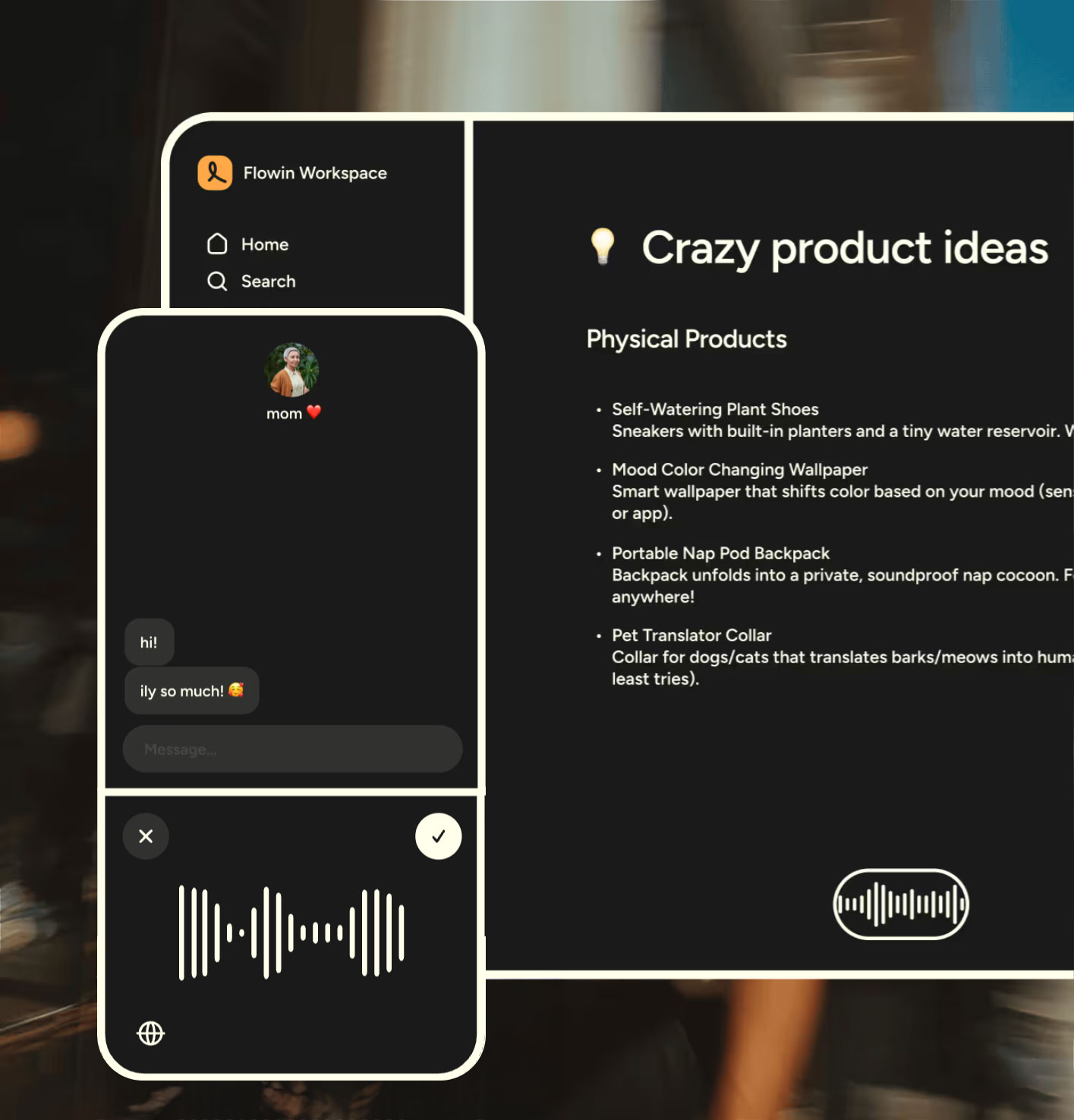

Riffsy is creating an evolving codex for short-form video that unlocks the world’s video library with one touch through an untapped portal: the keyboard. Despite a 19th-century UX and nonsensical configuration, the antiquated QWERTY keyboard has somehow survived and thrived, a testament to its subtle network effect. Given the fierce war being waged on our phones for every millimeter of homescreen real estate, it surprised us how little innovation the keyboard has experienced because of its prime location, access to all applications, proportional physical footprint, and user lock-in once installed.

The keyboard has been our gateway to communication since the creation of the typewriter, and the PC and mobile revolution have made it a centerpiece of our daily interactions. Since messaging is a time-critical and frequent use-case, the keyboard makes an ideal beachhead because it’s one degree of separation away from every conversation. Stitching together the fractured process of opening an app, finding a GIF, and sending it was not fluid enough, until Riffsy created a magical experience suitable for agile consumption.

The keyboard is synonymous with messaging and creation, but not with language. As GIFs and Emoji become standalone verbs, they should be accessible to any device. Consumers are tethered to phones today, but tomorrow it will be devices we’ve never even conceived of. The portability and flexibility of Emoji have already taken hold on the Apple Watch; with functions like Riffy’s Emoji search, GIFs are sure to follow. The keyboard is an insertion point to propagate Riffsy’s expression language, but it’s not the final destination. At four billion views a month and with half its users opening Riffsy five days a week, we’ve just begun to capture the groundswell of demand for the highlight reels of the Internet.

As Riffsy’s Co-Founder David likes to say, “3–5 seconds is the new 3–5 minutes on mobile.” Much the way WhatsApp piggybacked on phonebooks, Snapchat on contact lists, and Instagram on Facebook graph on their way to establishing a new standard, Riffsy has already overlayed across existing networks via an interface that touches every mobile application. Just as SMS became the de facto communication paradigm for written text, Emoji for images, and Skype for video, we believe Riffsy will create the analog for visual expression and turn Internet slang into a worldwide lexicon.

So go ahead. Try it. You’ll see why we believe in David, Erick, and giving the gift of GIFs to Messengers everywhere.