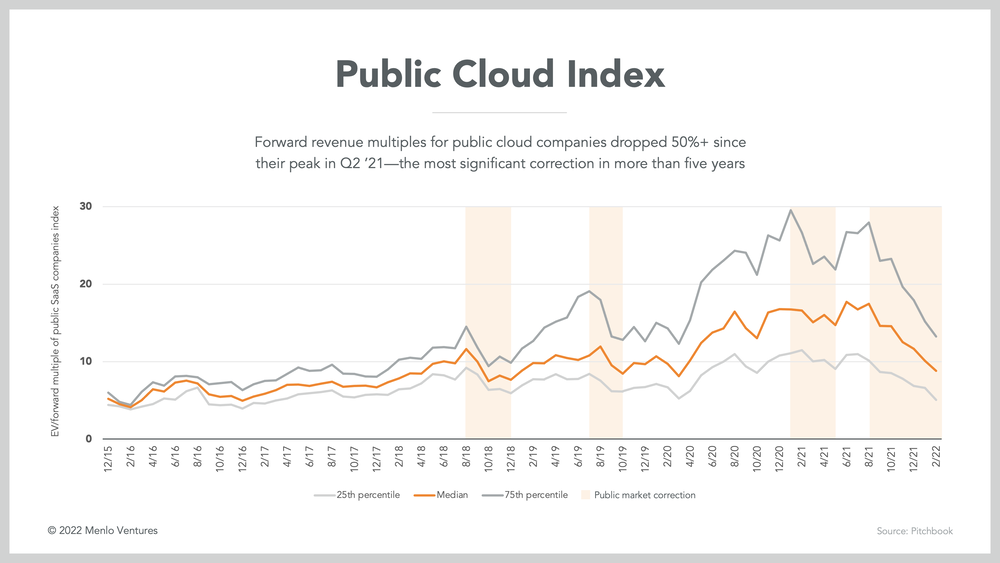

After nearly two years of soaring valuation multiples for public cloud stocks, the law of financial gravity has returned in recent weeks.

A changing monetary environment and volatile geopolitical backdrop is spurring large capital outflows from high growth SaaS stocks and significant public market turmoil. Public cloud stocks are down more than 50% from mid-2021 highs: Adobe dropped 36%. Salesforce lost 33%. Zoom, 73%. Even the darling of the pandemic markets, Snowflake—which debuted in September 2020 as the largest ever software IPO, and then continued to grow 100%+ YoY—has shed 48% of market cap off its 52-week high.

Such public market turbulence makes for a confusing fundraising environment for startups and early-stage investors who look to public markets to benchmark valuations via metrics like forward revenue multiples. Price movements in public markets, after all, eventually trickle into private markets with time as investors consider the market conditions they’re exiting into.

So what happens when these public comps fall 50%+ in the span of a few weeks?

If History Is Any Guide…

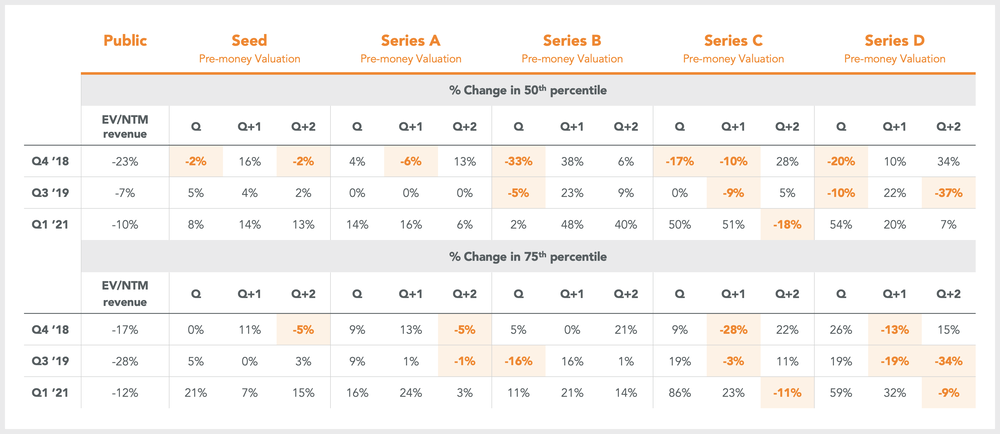

According to recent historical precedents, the answer depends on the company’s scale and growth profile.

Earlier stage companies (Series A and B) and those with more “premium” records of execution will remain insulated from public market oscillations for longer. For these groups, private valuations often do not show any signs of correction until two or three quarters after a public market dip.

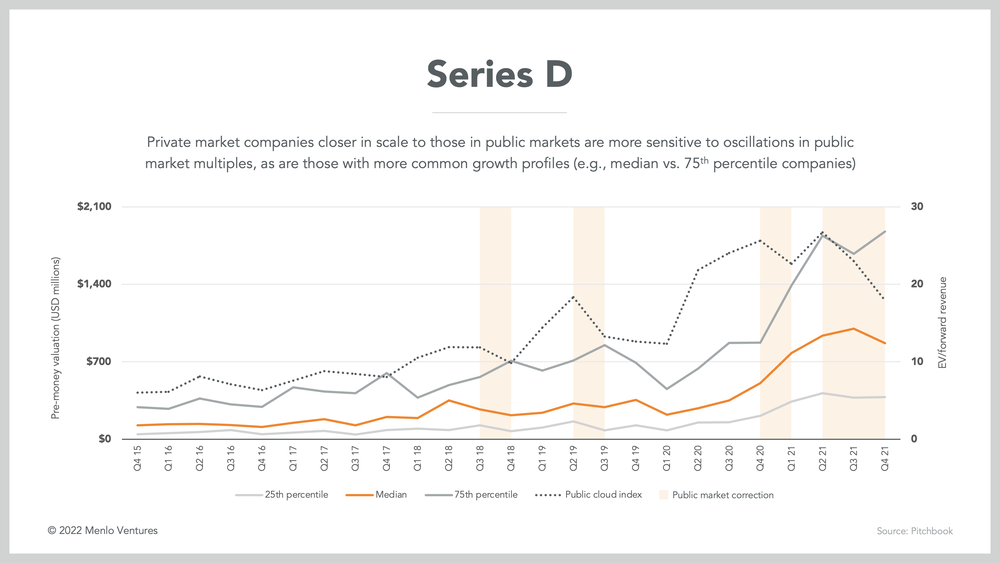

Those closer in scale to public companies and with median growth numbers, on the other hand, will feel the impact of the recent multiples contractions first—often in the same quarter or just one quarter after a public market contraction.

Using private market funding numbers from Pitchbook across the past five years as our guide, we arrived at our findings by examining the performance of median and 75th percentile valuations across seed to Series D rounds in the two quarters following a public market contraction. (Granted, these corrections each proved more shallow, and short-lived, than what we are seeing today—but the private market impact is sufficient to illustrate our point.)

Looking at median Series D valuations first, the impact of the Q4’18 and Q2’19 public market contractions were almost immediately felt: Median pre-money valuation contracted 20% and 10%, respectively, in the same quarter compared to the previous one, against median EV to forward revenue multiple contractions of 23% and 7% in public markets.

The Q1’21 reset doesn’t follow this trend as closely, though the “contraction” in this quarter was more so a stabilization of the stratospheric multiples growth earlier in the year. Growth in median round size quarter-over-quarter slowed, and eventually reversed in Q4’21.

This is a different story than for more premium companies during this time that also raised a Series D. While median valuations were down in Q4’18 and Q2’19, 75th percentile valuations increased in the same quarter. We did not observe downward pressure from public markets until one quarter later, when valuations dropped 13% and 19%, respectively. In the case of Q2’19—a more significant downturn that is more reflective of today’s situation—it took two quarters to fully reflect the 28% single-quarter drop in forward multiples.

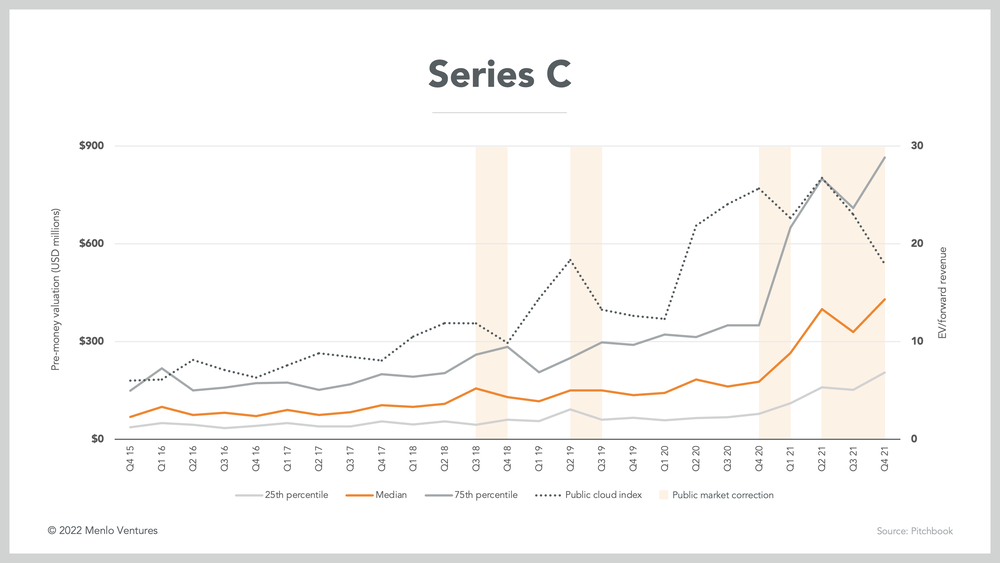

This acuteness of public market turbulence softens as we move to earlier fundraising stages. Both median and top quartile Series C valuations tend to reflect public market repricing with a quarter lag.

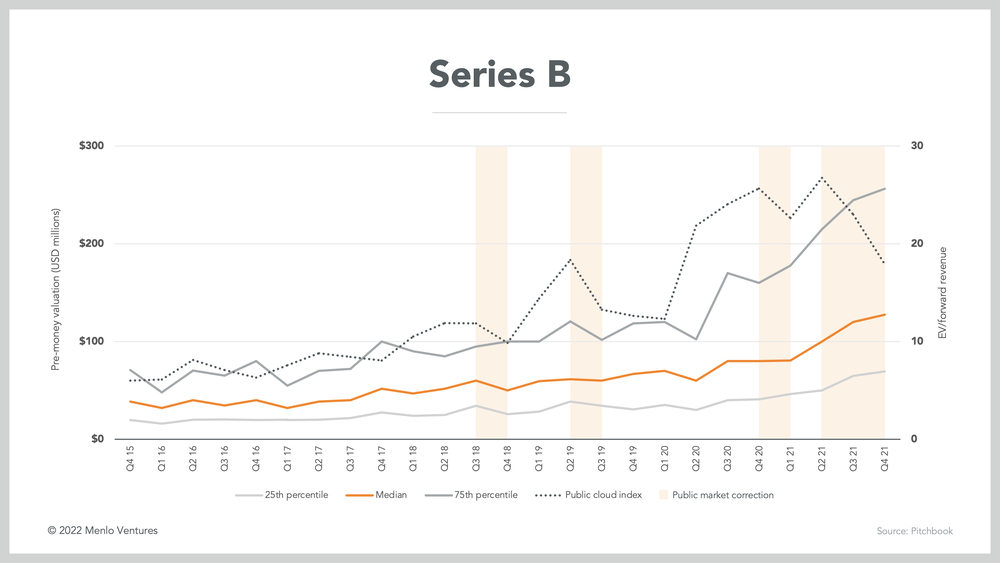

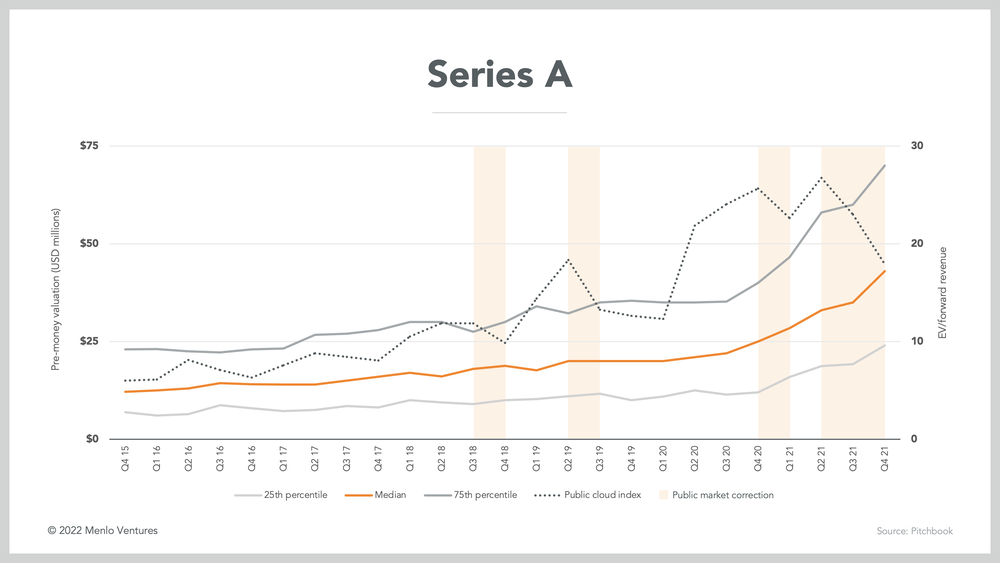

By the time we get to Series A and B—the stages at which Menlo Ventures most often invests—we see two quarters or more of lag. In Series A, in fact, corrections in the past five years in public markets have led to temporary momentary slowdowns in valuation growth but no sustained reversals.

Fundraising in the Post-Pandemic Private Markets

As SaaS founders survey the private fundraising environment today, these trends suggest the need for differing responses for late-stage startups versus their early-stage peers, as well as median- versus high-growth players.

For late-stage companies, the decline of investor appetite and software prices is happening now. Crossover funds that poured billions into pre-IPO companies during the pandemic and drove valuations sky-high have already signaled a pullback amid anticipated underperforming public market exit options.

Leading investment banks for software initial public offerings are advising clients to delay public listings or anticipate lower valuations, and Justworks and WeRock have already put off planned public debuts, citing market conditions.

The top priority for late-stage companies with additional capital needs in the coming quarters should be demonstrating tangible business progress in hopes of growing into their now-rich valuations. After a period of exuberant prices that at times exceeded fundamentals, the bar will be higher now in terms of recurring revenue momentum, customer traction, and unit economics. Higher margins and lower cash burn also become more attractive as late-stage investors adjust back from their recent over-rotation towards growth versus profits.

For founders seeking to continue to raise large early rounds, there is a good likelihood that private market enthusiasm will persist for at least a few more months before the downward pressure of public markets begins to settle in.

To be clear, falling public multiples are already top-of-mind for us at Menlo as we think about private-market entry prices. Since the start of the year, every valuation has begun with the acknowledgement that the inflated private transaction comps of the previous two years are now at odds with the current public pricing environment. For the median early-stage company, corrections are coming, whether this quarter or next.

But for the best early-stage startups, valuations look to remain elevated for the foreseeable future. Early-stage investors now sit on a record amount of fresh dry powder that still needs to be deployed after raising $96 billion in new capital in 2021—not including Tiger Global’s new $11 billion venture fund, or Andreessen Horowitz’s $9 billion, both of which were announced this year.

These funds have been put to work earlier and earlier in the startup lifecycle, both as a means for deploying more capital and a way to win allocation in later rounds on the best companies. It was telling that in the same breath that Tiger announced its withdrawal from late-stage private markets, the fund also said it would redirect that capital to early-stage ventures.

This answer isn’t simply a matter of capital overabundance though. Competition may be the proximate driver, but high valuations are ultimately justified by investors’ conviction in whether entrepreneurs are building truly iconic companies. If so, short-term multiples fluctuations take a backseat to the signal for what could become the next fund returner. In the end, these will be the companies still raising at high valuations three quarters from now.

Steve is a partner at Menlo focused on investments in Menlo’s Inflection Fund, which targets fast-growing Series B/C companies. He specializes in AI-powered vertical SaaS investments and supply chain technology, including Enable, Eleos, Observe.AI, Scout, 6 River Systems, ShipBob, CloudTrucks, and Parade. Steve joined the firm in 2015 as an…

As an investor at Menlo Ventures, Derek concentrates on identifying investment opportunities across the firm’s thesis areas, covering AI, cloud infrastructure, digital health, and enterprise SaaS. Derek is especially focused on investing in soon-to-be breakout companies at the inflection stage. Derek joined Menlo from Bain & Company where he worked…