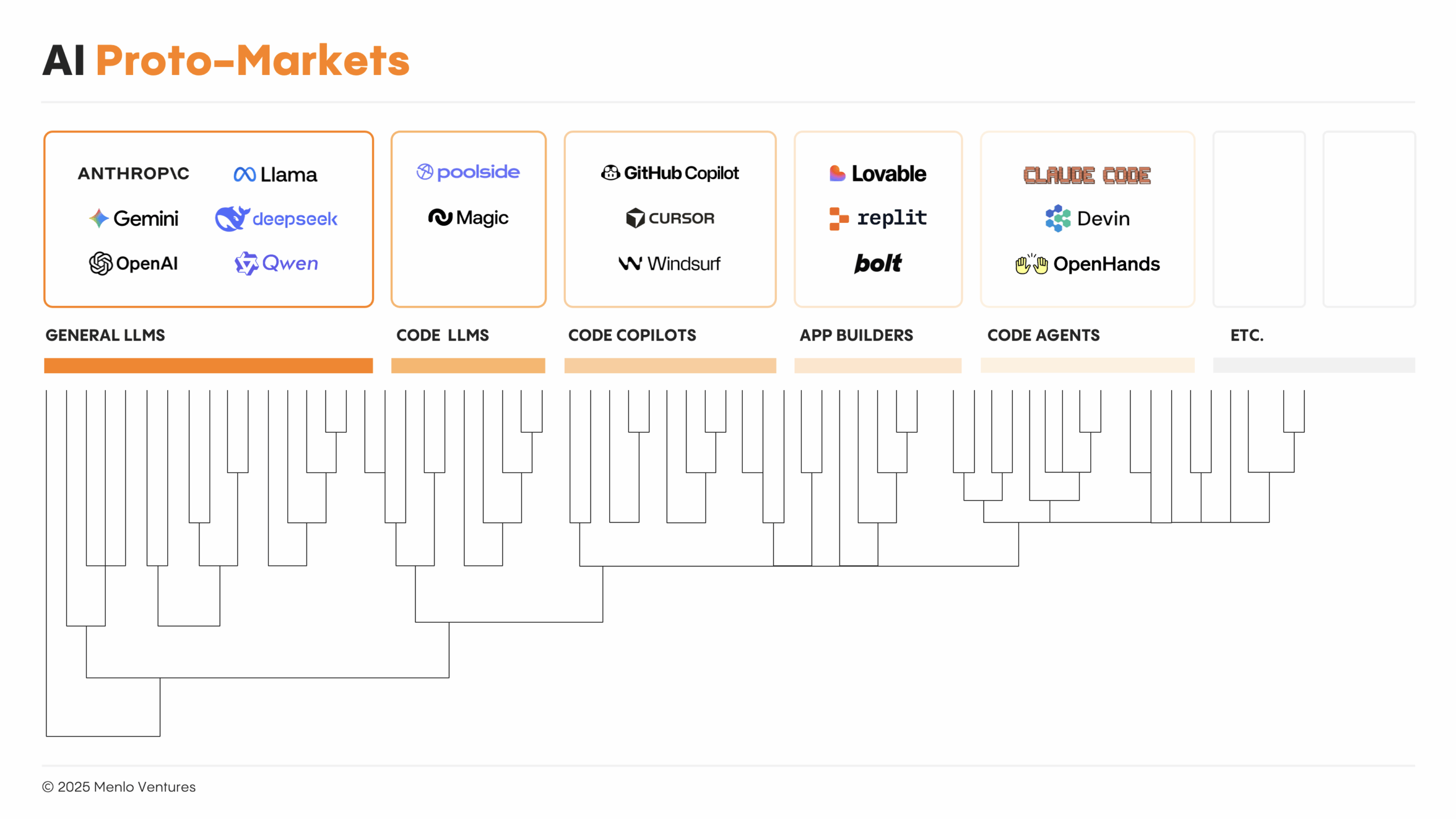

Today’s AI markets are noisy. Code generation, customer support, and legal each have five-plus credible leaders; emerging categories have dozens more overlapping products with little apparent differentiation. By traditional software standards, none of this looks like the foundation for enduring outcomes: no moats, no margins, no market boundaries or barriers to entry.

But this is the wrong lens. AI markets feel chaotic because they are not markets at all. They are proto-markets: evolutionary precursors where demand exists but selection and speciation have yet to take hold. Despite revenues already rivaling those of fully formed markets, they remain structurally unfinished.

The distinction is important because winning in proto-markets looks different than winning in a mature SaaS market. Where demand is defined and technology is stable, generational companies find moats early and compound them into margin and market leadership over time.

In proto-markets, that playbook is premature. What wins instead is product plasticity and learning velocity—the flexibility and speed at which user behavior becomes product improvement. The winners will be products that explore widely, capture user signals, and convert early learning into AI’s first durable moats.

Defining AI Proto-Markets

Early AI categories may have the revenue scale of mature SaaS, but little else in common. Across several characteristics that fully formed software markets take for granted, AI proto-markets are still evolving.

- Capabilities blur market boundaries. Traditional software has well-defined edges: enterprise vs. consumer, horizontal vs. vertical, sales vs. marketing vs. HR. AI’s broad generalizability collapses these distinctions without leaving clear definitions for what a single product should do. Salesforce’s Agentforce and ServiceNow’s NowAssist compete not only on each other’s home turfs of sales and IT, but also offer agents for customer support, recruiting, finance, and enterprise search. Sierra began as horizontal customer support before extending into both patient engagement and RCM to become healthcare’s leading voice AI solution. Lovable* defined itself in consumer markets before being pulled into the enterprise.

- Products are never “done.” Claude Sonnet 4.5’s release prompted Cognition to rebuild Devin entirely. The model’s new behaviors broke previous assumptions about how the agent harness should interact with the model’s context window awareness, file system note-taking, and tool use. Manus has reconstructed its own agent framework four times. When the foundation keeps shifting, there is no stable “definition of done” for any AI app category.

- Unit economics remain unsettled. The division of value between end users, AI applications, and underlying foundation model has not yet equilibrated, making current economics a poor guide for long-term market structure. In categories like code and voice AI, many solutions are priced at or below cost. Falling token prices and margin optimization will eventually reset these dynamics, though the steady-state outcome remains uncertain.

- Competition is with the status quo, not other products. AI markets are so large that, despite rapid adoption, most remain greenfield. Buyers are still more often comparing something to nothing, rather than two head-to-head AI vendors. It’s why even seemingly niche markets like home services that only ever produced one major SaaS outcome (ServiceTitan) now seem to be able to support an ever-expanding number of fast-growing startups: Rilla, Siro, Avoca, Netic, Probook.

- Adoption is bottoms-up. In AI, product-led growth is less a go-to-market choice than a way to learn how users actually use products before buyers, budgets, and requirements settle. From Cursor* to ElevenLabs to Gamma, leading AI products have reached massive scale through this channel. But without product-led sales motions, this adoption lacks the organization-wide stickiness SaaS locked in much earlier.

The Case for Exploration

Given the uncertainty in AI proto-markets, the SaaS playbook—moats first, then margins, then market leadership—is not just difficult, but actively wrong. The list of heavy upfront research and engineering efforts that have failed to become durable sources of differentiation at the AI app layer is long: proprietary foundation models, domain-specific fine-tuning, sophisticated search architectures like Monte Carlo Tree Search.

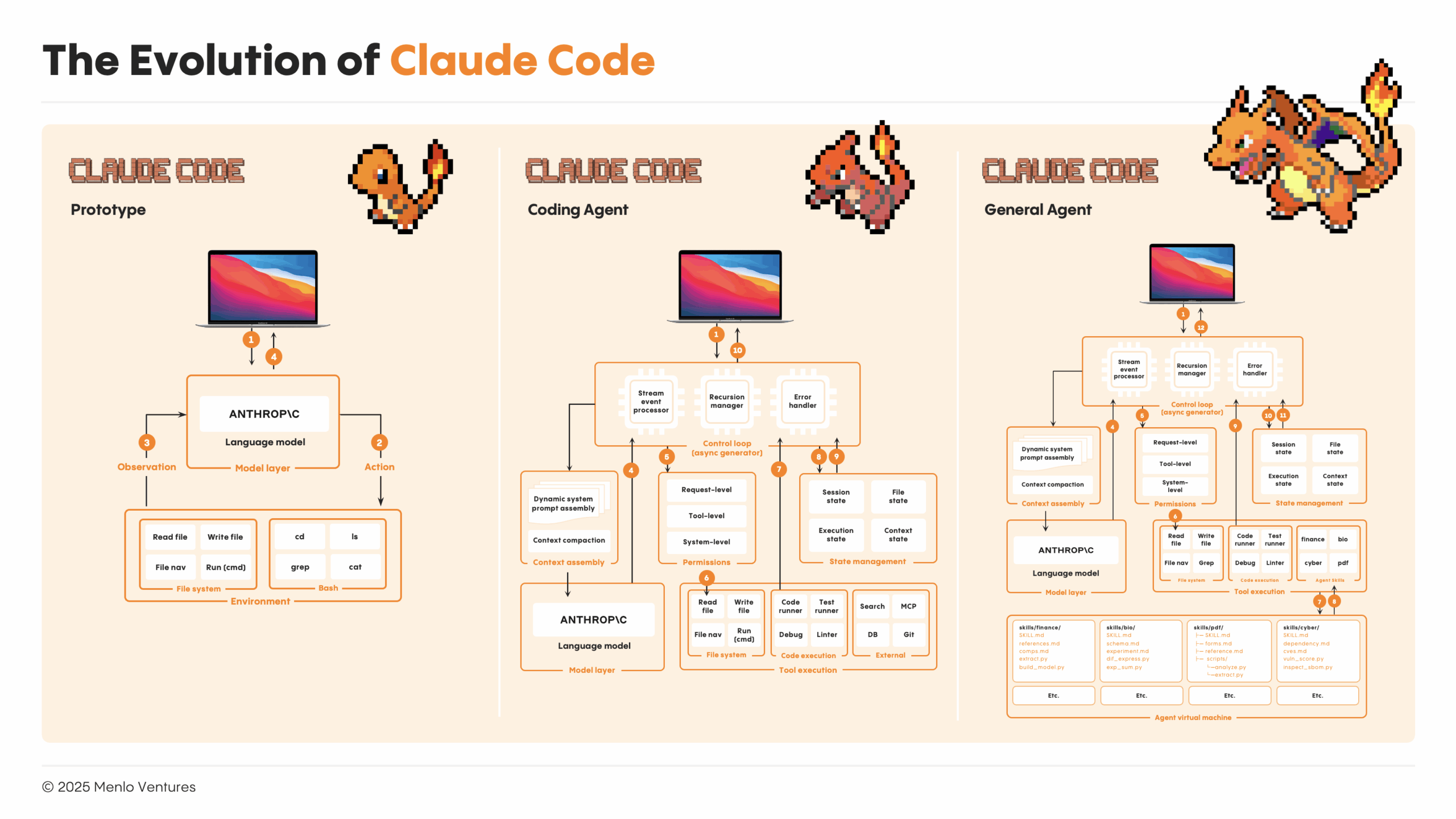

What early markets are rewarding instead is product plasticity and learning velocity. At Anthropic*, Boris Cherny—the creator of Claude Code—calls this building products that are “hackable by design.” Start with the simplest thing that works.

Claude Code was conceived this way: a Unix-like utility with no UI, editor integrations, or abstractions—just a chat loop wired to shell and the filesystem. Instead of bespoke configurations, just a markdown file (claude.md) auto-loaded into context. Instead of integrations, direct directory access. Instead of custom tools, bash.

Then they watched what users did with it.

Power users often created plans before coding. Anthropic productized that pattern into Plan Mode (/think). The model occasionally self-organized work into markdown checklists. That became the to-do list abstraction. Users built libraries of executables to adapt Claude Code to different domains. That evolved into Agent Skills.

The extension surface expanded based on observed behavior: permissions systems, hooks that let users intercept model actions, slash commands, sub-agents. Each addition formalized something users were already hacking together.

Evolving Toward AI’s First Moats

In AI, markets emerge before moats do. In these still-evolving categories, the evolutionary approach to product development does more than iteratively improve the product. It creates a path-dependent advantage that, in aggregate, becomes AI’s first durable moats.

Early users explore features and discover what works and what doesn’t. That learning is then encoded into the scaffold of the product itself—patterns, workflows, and constraints that shape how the model behaves. By the time selection pressures sharpen and market boundaries harden, this understanding is structural.

Seen this way, AI’s first moat is the accumulated understanding of what users actually need. The builders who win will treat every user interaction as raw material—captured in ontologies, decision traces, and learning loops—and compound it into a lasting advantage before the market is even fully formed.

* Menlo portfolio company

As a principal at Menlo Ventures, Derek focuses on early-stage investments across AI, cloud infrastructure, and digital health. He partners with companies from seed through inflection, including Anthropic, Eve, Neon, and Unstructured. Derek joined Menlo from Bain & Company, where he advised technology investors on opportunities ranging from machine learning…